Last month I did a talk about Romeo and Juliet, Verona, tourism and fascism at History Showoff, a fun night where a bunch of historians get up in a pub basement and have exactly nine minutes to share something interesting with the audience. Although I am not a proper historian, the organiser let me have a go anyway (thank you Steve!), and I think it went well. There’s a video on YouTube (and below), although I could only watch 30 seconds of it before turning it off, because I hate hearing my own voice!

Here’s the gist of it, adapted from my notes, though I realised while putting this together that I didn’t really keep track of citations, since I wasn’t thinking past the presentation (see again: not proper historian). So there are some parts in the talk that aren’t here (mostly jokes about TripAdvisor) and some parts here that aren’t in the talk (mostly because I was nervous and forgot).

If you want to read more from actual researchers, my main sources were: The Renaissance Perfected: Architecture, Spectacle and Tourism in Fascist Italy (2004); ‘Form Follows Fiction: Redefining Urban Identity in Fascist Verona through the Lens of Hollywood’s Romeo and Juliet’ in New Perspectives in Italian Culture Studies: The arts and history (2012); and, of course, Letters to Juliet (2006).

‘Benito and Juliet’: A short history of Shakespeare tourism in Verona

Just to be clear, Romeo and Juliet Definitely Didn’t Happen

It’s worth underlining that Romeo and Juliet is a completely made-up story. It’s based on a 1476 novella about two youngsters in Siena named Mariotto and Gianozza, who want to marry quickly and secretly (no reason! …sex reasons), and find a friar to do it. A few days later, Mariotto argues with another citizen, kills him and is banished, while Gianozza’s father starts pressuring her to marry another suitor. She goes to the friar for a fake-death potion, sends a note to Mariotto to tell him what’s happening, and drinks it. The note goes missing; Mariotto hears his wife is dead and rushes back to Siena; everyone dies.

In 1530, a soldier-turned-writer named Luigi da Porto lifted the story and set it in Verona in early 1300s. He renamed the lovers ‘Romeo’ and ‘Giulietta’, and added the detail of feuding families named Montecchi and Cappelletti, names he borrowed from Dante’s Purgatory. But – there’s no record of a Cappelletti family ever living in Verona, and although there were some Cappellos at about the right time, they weren’t feuding with the Montecchis, who anyway had mostly left Verona by the late 1200s.

What I’m getting at is that the story is demonstrably fiction, not even as in, ‘oh, we don’t know, it could have happened!’, but as in, ‘there is a clear direct literary source for this, which has totally different names and takes place hundreds of miles away and a century and a half later, and the families that were supposed to be ‘historically feuding’ either never lived there or didn’t live there at the same time’. I know I’m hammering this point but it’s quite important with what people say about the story later to remember that it is very very fictional.

The beginning of Romeo and Juliet tourism in Verona

In the 1590s Shakespeare wrote a quite good and popular play about the story, and then in the next two hundred years became a massive icon of English culture and Good Art. Also during those two hundred years, travel within Europe became easier and more common, and lots of English people started travelling to Italy for cultural tourism. By the late 18th century, the city of Verona had identified an attractive sarcophagus in a church garden, which they were calling ‘Juliet’s tomb’, mostly because literary English people on the Grand Tour kept popping in and asking about it.

Official postcard of Juliet’s Tomb, early 1900s

The tomb became quite well-known: Byron nicked a few small pieces for his ‘daughters and nieces’ (yes – Ada Lovelace probably owned a small chunk of it!), and Dickens visited in 1846, writing:

I went off, with a guide, to an old, old garden, once belonging to an old, old convent, I suppose; and being admitted, at a shattered gate, by a bright-eyed woman who was washing clothes, went down some walks where fresh plants and young flowers were prettily growing among fragments of old wall, and ivy-coloured mounds; and was shown a little tank, or water-trough, which the bright-eyed woman – drying her arms upon her ‘kerchief, called “La tomba di Giulietta la sfortunáta.” With the best disposition in the world to believe, I could do no more than believe that the bright-eyed woman believed; so I gave her that much credit, and her customary fee in ready money.

That there were two separate guides, one with a ‘customary fee’, implies it was a regular tourist stop – I love that woman at the tomb, by the way, she is totally nailing the ‘milk English writers out of their holiday lira’ routine.

I can’t figure out exactly when ‘Juliet’s House’ was first ‘identified’ for tourists, but it’s based around a building with a hat (cappello) carved into the stone entry way:

Photo by Lo Scaligero, licensed under CC BY 3.0

It may have belonged to the Cappello family, or been a hatmaker/milliner’s home or shop – either way, there was demand for a place called ‘Juliet’s house’, and the connection of ‘hat – cappello – Cappelletti – Juliet Capulet’ was enough to make it this building.

1930s interest in Romeo and Juliet sites

‘Juliet’s house’ went up for sale in 1905, and the city of Verona bought it after a public campaign led by the local daily newspaper L’Arena. In 1937-8, the city spent a massive amount of public money on ‘restoration’ works for both the house and the tomb.

I was quite curious about what triggered the investment in the late 1930s specifically, and there turned out to some very good reasons why the civil government of Verona wanted to invest in Romeo and Juliet tourism sites at that time.

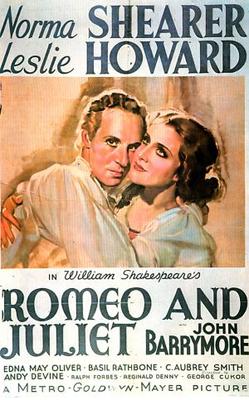

First, a Hollywood film version of Romeo and Juliet came out in 1936. It was a big-money prestige project for MGM – George Cukor directed, A-listers Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer starred, and John Barrymore, noted stage actor (TM) played Mercutio – and the studio really wanted it to be taken seriously as Proper Art. Before production, MGM sent location scouts to Verona to take photographs, sketches and notes about the city, to see if it was possible to actually film the movie there, or if not, to get material to recreate an authentic ‘Verona’ in a Hollywood lot.

This got the attention of the Italian government, who realised that a big American film project focusing on Verona could be a great way to direct favourable international attention to Italy’s cultural heritage. And the reason the Italian government of the 1930s was so keen on getting good international attention for Italy and Italian history – and I can’t believe it took me so long to put the dates together – was that the government at the time was, of course…

…wait for it…

…prepare for some amazing Photoshop…

Mussolini’s Fascists!!

(isn’t this amazing? I paid a guy £7 on fiverr.com to make it for me. best £7 I have spent possibly ever.)

So when MGM requested visas for location scouts with an eye to possibly filming a prestigious Shakespeare film in Verona, the Fascist government was THRILLED – they loved anything that made Italy look good and important, and they especially loved it when people paid attention to the Renaissance, a time when Italy was seen as being the best and most important place in the world. A big part of fascist mythology is the idea of recreating or returning to a great lost time of glory – like British fascists idealising a past all-white island that was ‘destroyed’ by immigration, or US politicians calling to ‘Make America Great Again’ – and for Italian Fascists in the 1920s and 30s, the Italian Renaissance was one of those Great Lost Times.

What I think is really interesting is how both MGM and the Fascist government were using each other to get credibility: the studio was trying to get cultural capital by recreating ‘authentic’ Renaissance Verona, and the Fascists trying to get political capital from the very fact that America’s biggest entertainment industry was looking to Renaissance Italy as a source of valuable authenticity. (I was also surprised at how easily Shakespeare was accepted as a source of credibility for both of them – I expected the Italians to put up more of a fuss, as he’s English, but I guess it shows just how significant the global weight of ~Shakespeare~ was and is.)

MGM decided against filming in Verona because it looked like war in Europe was going to break out any day, but the movie still drew lots of attention to the city, and individual tourists were still coming. After the film premiered, the city decided to do up the Romeo and Juliet-related sites. Verona’s superintendent wrote to Italy’s public education minister (who approved restoration budgets) arguing the importance of ‘attracting tourists, especially foreign ones, and reinforcing the link between Verona and the two lovers’, and the budget approval highlighted Juliet’s tomb as ‘one of the most visited monuments in Verona, especially by foreign tourists’. Again – not to do up the sites as places of historical interest in their own right, but explicitly and specifically to attract foreign tourism.

1937-8 works on ‘Juliet’s tomb’ and ‘Juliet’s house’

The works were led by Verona’s civic museums director, Antonio Avena. Juliet’s tomb in the leafy corner of a convent garden had been a tourist site for centuries, but Cukor’s film set the tomb scene underground – so Avena dug a brand-new crypt, and decorated it with the aim of looking like the scene in the film. Two 15th-century window frames were installed above the tomb; they had been ripped out of a nearby 15th century building, which was demolished. The ‘Gothic’ rose window above them was completely new. The attractive shaft of sunlight is also from a hidden spotlight – I don’t know when it was installed, I only noticed it when I visited (in July 2015). (Also sorry for the wonky camera angle, it’s a tight space!)

The entrance to the crypt has a collection of tombstones to make it look more like a family mausoleum, since in the play Juliet was buried in the Capulet crypt. The tombstones were just taken from nearby graves, which are now unmarked; there is no one buried beneath them.

At ‘Juliet’s house’, the courtyard was cleaned up and the outer wall reconstructed, with arched windows added to make it look more medieval-y. There was no balcony, so – this is my absolute favourite part – Avena just grabbed a 14th-century sarcophagus from Castelvecchio, another ‘restoration’ project he was supervising, and sawed it in half and stuck it below a window.

Repeat: HE GLUED A HALF-SARCOPHAGUS ONTO THE WALL.

AND NOW PEOPLE STAND ON IT AND GO OOH OOH ISN’T IT ROMANTIC

TOURISM IS SO WEIRD.

The city also put up engraved quotes from Romeo and Juliet around Verona – my favourite part of this is the fakey classical ‘V’s in ‘Jvliet is the svn’, which almost give the impression that the Italian is the original, and the Shakespeare is the translation.

Avena wanted to fill the house with props, costumes and sketches from the MGM film, but the studio didn’t want to send them over to Italy, again because of being worried about safety. It really kills me that his focus was on the props from the movie – it’s almost like those valuable artefacts were more important than the actual history he was partially demolishing to construct these made-up tourist sites.

Verona after 1938

Juliet’s house and tomb look basically the same today as they did when Avena finished, give or take the odd spotlight or statue (the bronze Juliet in the courtyard is from 1972).

In 1943 Mussolini was removed from power in Italy and imprisoned, and quickly ‘rescued’ by the Germans and set up by Hitler in a quite pathetic little puppet government based in Salò, about 30 miles from Verona. A lot of his ministries, including the ministry of culture, had their offices in Verona, and for this reason Verona was bombed quite heavily by the Allies. Avena, who stayed in his job until retiring in 1955, risked his life several times to help put out fires caused by the bombings at historical sites in and around Verona. I really can’t get a grip on Avena; he was so careless about the integrity of the sites themselves but so careful about them after he’d finished with them.

The punch line is after all that work aimed at impressing literary travelers and showing off the city’s valuable cultural heritage, the Juliet sites are now pretty widely perceived as tacky tourist traps – the house is the #56 TripAdvisor ‘thing to do in Verona’ and the tomb is an embarrassing #134 out of 159. As if we needed another reason to think fascist governments are a bad idea.